How beautiful it is to do nothing, and then to rest afterwards. ~ Spanish proverb

We won’t be gathering Sunday morning, March 29 at the OM collective. Do nothing, rest, and welcome the morning light of early spring. Also… please practice.

On Saturday, October 5, those of us gathered in the Meditation Center’s puja room were gifted with the thoughtful, kind, and inspiring presence of Pandit Tejomaya. Travelling to us from his Island of Peace Yoga center on Gabriola Island—in the Salish Sea off the coast of British Columbia, Canada—Pandit-ji came to share his reflections on some core teaching of the Yoga Sutras and on his experience developing what for him has been an intense, years-long practice of the yamas and niyamas.

On Saturday, October 5, those of us gathered in the Meditation Center’s puja room were gifted with the thoughtful, kind, and inspiring presence of Pandit Tejomaya. Travelling to us from his Island of Peace Yoga center on Gabriola Island—in the Salish Sea off the coast of British Columbia, Canada—Pandit-ji came to share his reflections on some core teaching of the Yoga Sutras and on his experience developing what for him has been an intense, years-long practice of the yamas and niyamas.

It’s probably safe to say that none of us thought the workshop would involve marshmallows or pie charts. But Pandit-ji’s graceful discussion of the meaning of yoga and its relationship to things like vrttis, the kleshas, karma, the accumulation of samskaras (rather like piles of minimarshmallows, don’t you think?), and the percentage of the Yoga Sutras devoted to each of Pantanjali’s eight limbs (enter the pie charts) showed us how. All this was to point out that, if we wish to achieve yoga, we’ve got a lot of practice to do, and coming up with practical ways of pursuing the yamas and niyamas is likely part of that.

Pandit Tejomaya’s own practice of the yamas and niyamas, he told us, is grounded in key insights from Swami Veda Bharati and Swami Rama of the Himalayas, including the ideas that progress in yoga involves studying oneself at the level of action, speech, and mind/thought; that this progress takes self-discipline; and that true knowledge comes from direct experience. And the practice itself? Pandit-ji takes one of the yamas or niyamas and makes a commitment to practice it in a particular, concrete way at one level (say, the level of speech) for twenty-one consecutive days. Then he moves on to practice that yama or niyama at another of the three levels (say, the level of action) for twenty-one consecutive days, finally advancing to the third level (mind/thought, for example) for (you guessed it) twenty-one consecutive days. Any mess-up puts him back to day one of whatever level he’s on. Success with one yama or niyama means choosing another, and starting the process from the beginning.

Intimidating? Maybe for some, but totally inspiring for others of us, and his gentle encouragement (and funny examples of his mess-ups) urged us to consider how we might craft similar practices for ourselves. Most of all, his very presence—graceful, serene, sincere—provided the inspiration, showing us, as it did, the end result of the devotion of a true yogi.

The purest consciousness in the highest level of meditation is a still consciousness. It is like a reservoir, like a forcefield, dynamic, vibrant but a very quiet vibration. . . . The pure consciousness in meditation is aware of itself. . . . It is like a flame, which, to prove to itself ‘I am a being of light,’ looks at all the illumination around it, which it itself is casting. ~ Swami Veda Bharati

A sweet and wise friend, Namita, shared a story with her Facebook pals that went something like this (I paraphrase—and switch up genders, just for fun):

One day, a young Buddhist, on her way home after a long journey, found herself before a wide and mighty river, one that impeded her progress. She spent hours on the bank, trying to figure out how to cross the great barrier.

Feeling hopeless about being able to continue on her journey home, she saw, on the opposite bank of the river, a venerable teacher. She called out, “Oh, wise one. Can you tell me how to get to the other side?” The teacher, thoughtfully considering her answer, called back, “My child, you are on the other side.”

Maybe I find this story so poignant because I just returned home from a two-week-long journey (and very, very nearly missed the return flight). But there’s something else here that strikes home (so to speak). It’s not quite the somewhat clichéd idea that wherever one is, one is already home, but it is close.

I am graced to know a few swamis—great meditators and teachers, each one—who share a common characteristic that I find pretty stunning: they are remarkably emotionally self-supporting. I see this most in their comings and goings. When they arrive from their international travels and teaching, they are filled with happiness and contentment at seeing those of us who welcome them. And when they leave us, they are filled with happiness and contentment in their going.

This has taken some getting used to. After all, one wants a friend, teacher, or loved one to grieve a bit when she leaves, to depart reluctantly, with sadness. But now I find it something to aspire to, since I see it as evidence of a valuable kind of emotional self-sufficiency, a kind of fullness that one feels in a home that is safe, warm, familiar, and welcoming. I, too, want to feel this, wherever I am.

Sometimes the barriers we face are wide and mighty external things like rivers, or wacky airline regulations and requirements, or the emotional reactions of other people. Sometimes they are internal, but no less wide and mighty: fear, doubt, anger, jealousy, laziness, and the like. How does one get home in the face of such obstacles?

For me, the answer is this: I practice. I sit, breathe, meditate, and find that stillness that is not a lack of something, but that is fullness itself, that is the full presence of the ever-wise inner teacher. Then I consciously impress what this feels like into my memory, so that when I venture out into the world again, I can always arrive back home, especially when it seems farthest away.

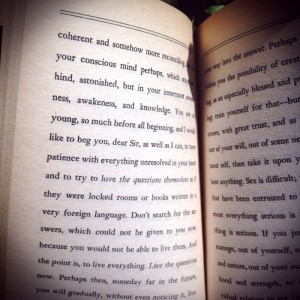

There is so much in the work of the late nineteenth-century, early twentieth-century German poet Rainer Maria Rilke that I find astonishing—that cracks open my everyday perspective, simply and powerfully. Some of his most accessible and moving (and now very well-known) words are in his letters to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young military student who was embarking on a career he wasn’t sure he wanted when he sent the famous poet a letter of introduction and a few pages of his own poetry. In one of his letters back to Kappus, Rilke writes,

There is so much in the work of the late nineteenth-century, early twentieth-century German poet Rainer Maria Rilke that I find astonishing—that cracks open my everyday perspective, simply and powerfully. Some of his most accessible and moving (and now very well-known) words are in his letters to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young military student who was embarking on a career he wasn’t sure he wanted when he sent the famous poet a letter of introduction and a few pages of his own poetry. In one of his letters back to Kappus, Rilke writes,

You are so young, so much before all beginning, and I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer. (Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, trans. Stephen Mitchell)

So again, here’s patience—with the mystery of our most unresolved, anguished questions, those lodged in our hearts as if locked in rooms or as if lying just beyond our comprehension on the pages of a seemingly (very) untranslatable book. Clearly knowing the discomfort of holding those questions himself, the poet gently advises his young friend to try to love them. Not to love them, but to simply try. And then to wait, maybe for a really, really long time, for the answers to become visible, tangible, livable.

For Rilke, the waiting erupted into poetry.

One of the biggest challenges for me in my practice of yoga has been that, when it comes down to it, the learning‚ the discovery, and the baby-step-by-baby-step resolutions are all essentially and fundamentally experiential. For an ex-academic inclined to hoard reference materials and to do impressive amounts of research before embarking on just about anything, this is a huge deal.

And this is why Rilke’s advice moves me, and why it is so important for me. Every time I close my eyes before meditation practice or move into an asana or slow and deepen my breath in pranayama, I am struck (I swear it often feels physical) by how “so much before all beginning” I am, especially in the face of the enormity of my endeavor and its importance. The practice and the reason for the practice are everything, and it is often like stepping into darkness; I cannot see where I am going. How I respond is my choice: I can turn back, I can fume, I can give into doubt, uncertainty, or fear, or I can present my questioning self, do what I know, wait, and cultivate patience. It’s not easy; I am waiting to “come into” the answer of the meaning of my existence—or more accurately, I am waiting for the answer to come into me, living in the urgency of the question, trusting that the answer will come, probably piece by piece, when my practice has prepared me to live it. And I don’t know when this will be.

Yoga philosophy, of course, promises that each of us already has the answers and they comes to us from within. So perhaps I should say that I wait for the answers to emerge into my self-awareness, to crack that perspective open so that I live everything even more fully than with the questions alone, as more of who I truly am.

If all of this is too heady, or all of this stuff about patience and waiting and emerging self-awareness just too wearing, we can come back to the things that the practice gives us as we do it. When it comes to meditation, the ongoing fruits are something like these (in the words of a master yogi and teacher):

Meditation will give you a tranquil mind. Meditation will give you awareness of the reality deep within. Meditation will make you fearless; meditation will make you calm; meditation will make you gentle; meditation will make you loving; meditation will give you freedom from fear; meditation will lead you to the state of inner joy called samadhi. These are the results of meditation. If you understand these goals and want to meditate, then it will help you… (Swami Rama, The Art of Joyful Living)

Rilke says in yet another letter, “What is happening in your innermost self is worthy of your entire love.” All the practice, the sitting with the questions, the trying to love them, the failing or the not failing . . . all of it is worthy of our deepest devotion—every drop of it. For each of us is, after all, so worth being, and so worth waiting for.

Earlier this week, I came across a quotation that picked me up, shook me around a bit, and then plopped me back down. (I love when this happens.) In the book The Spirituality of Imperfection (a title that, when I first saw it, already gave me the “this is important” shivers), Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketcham write,

We modern people are problem-solvers, but the demand for answers crowds out patience—and perhaps, especially, patience with mystery, with that which we cannot control. Intolerant of ambiguity, we deny our own ambivalences searching for answers to our most anguished questions in technique, hoping to find an ultimate healing in technology.

I am certainly a problem-solver and answer-demander, but have always thought that I scored pretty high on the patience scale. I’ll stick to a task until it’s done. I’ll go slow and steady if I have to. I’ll be the one to cross the finish line, to get the degree, to bide my time until an answer is confirmed. That’s patience, right?

Well, maybe. Sometimes. But other times it’s just willful stubbornness laced with “I’ll show you” and spiked with exactly what Kurtz and Ketcham find to be such a problem: an intolerance of ambiguity (as in, “What do you mean ‘Will this work?’ Of course this will work. I’ll show you—even if it kills me.”). I know this pattern in myself. It’s what got me through graduate school. But I’m not all that comfortable with it anymore. I’m much more interested in cultivating true patience, even (and perhaps especially) patience with mystery.

There doesn’t seem to be one term in Sanskrit that captures just what we mean by the term “patience.” Abhaya points to the fearlessness that patience sometimes requires, and dhairya denotes firmness or steadiness, which captures another aspect of patience. But kshama may be closest, as it can mean forbearance, a term often used in English as a synonym for patience. Like most Sanskrit terms, however, it’s meaning is layered, for it also means forgiveness.

So to have patience with yourself or another person is not only to forebear frustration, or discomfort, or whatever feeling the situation triggers in you, but to also forgive. How difficult, but how beautiful.

Even with our more basic understanding of patience, we tend to find it difficult to cultivate. We’re problem-solvers, sure. But yoga philosophy suggests an even deeper root: attachment. Our setting of expectations, and our attachment to finding “solutions”—especially solutions outside of us—precede the problem-solving. We wonder why we’re not happy, and turn to certain other people or things to solve the problem. When that doesn’t work, we turn to yet more people—or jobs, or cities, or pieces of pie, or whatever.

Why? Kurtz and Ketcham suggest that we’re intolerant of ambiguities and we deny our own ambivalences. I think they are on to something. We’re uncomfortable in that place of suspension, feeling an equal pull between two opposites. We’re uncomfortable fluctuating between what strikes us true but what could be false, between something we find both attractive and unattractive. When we’re stuck in the middle of a river, we tend to call whichever bank seems closest the “right” or “best” bank.

In our meditation practice, this intolerance can show up as giving up on certain techniques or sitting postures—or giving up the practice altogether—when we don’t experience exactly what we expect. But of all things, meditation puts us face to face with mystery, and to complicate this mystery, we often look to meditation to answer our most anguished questions: Who am I? What is my purpose? And so meditation is the quintessential activity for the cultivation of patience. Journeying into—and beyond—the unconscious mind, with all the other things that this requires and entails, means bumping into ambiguity after ambiguity after ambiguity. And while we can learn of the meditative experiences of others, ultimately our own experiences will be absolutely unique. Others can provide a kind of roadmap, but we must take the steps. What those steps will be like for each of us depends on who we are. And self-discovery takes patience.

I don’t mean to suggest that we should stick with something or someone if it isn’t working for us or if it’s harmful. But as one of my teachers is fond of saying, the mind is like a laboratory, and as meditators, we are scientists of the mind. The best scientists don’t assume what they’ll see; they formulate hypotheses. They don’t demand solutions; they test and observe. And then they test and observe again. This technique of problem-solving doesn’t crowd out patience; rather, it requires it and allows it to flourish. And it helps scientists see their way forward.

These days, as I take my meditation seat, I practice that kind of patience, the patience of the explorer, the patience of the scientist. I test and observe and forgive myself my flares of impatience, all the while keeping an eye on the roadmap of the great meditators who say that, as one practices in this way, the highest part of the mind, the buddhi, the intuitive intelligence, helps guide the way.