We will not meet for the Sunday morning integrated practice on March 9, 16, and 23.

We will not meet for the Sunday morning integrated practice on March 9, 16, and 23.

Please come on March 30 to celebrate the light of spring!

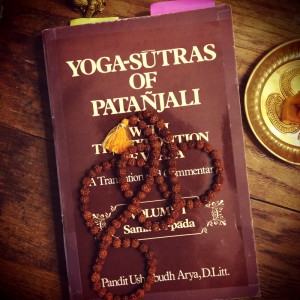

On Saturday, October 5, those of us gathered in the Meditation Center’s puja room were gifted with the thoughtful, kind, and inspiring presence of Pandit Tejomaya. Travelling to us from his Island of Peace Yoga center on Gabriola Island—in the Salish Sea off the coast of British Columbia, Canada—Pandit-ji came to share his reflections on some core teaching of the Yoga Sutras and on his experience developing what for him has been an intense, years-long practice of the yamas and niyamas.

On Saturday, October 5, those of us gathered in the Meditation Center’s puja room were gifted with the thoughtful, kind, and inspiring presence of Pandit Tejomaya. Travelling to us from his Island of Peace Yoga center on Gabriola Island—in the Salish Sea off the coast of British Columbia, Canada—Pandit-ji came to share his reflections on some core teaching of the Yoga Sutras and on his experience developing what for him has been an intense, years-long practice of the yamas and niyamas.

It’s probably safe to say that none of us thought the workshop would involve marshmallows or pie charts. But Pandit-ji’s graceful discussion of the meaning of yoga and its relationship to things like vrttis, the kleshas, karma, the accumulation of samskaras (rather like piles of minimarshmallows, don’t you think?), and the percentage of the Yoga Sutras devoted to each of Pantanjali’s eight limbs (enter the pie charts) showed us how. All this was to point out that, if we wish to achieve yoga, we’ve got a lot of practice to do, and coming up with practical ways of pursuing the yamas and niyamas is likely part of that.

Pandit Tejomaya’s own practice of the yamas and niyamas, he told us, is grounded in key insights from Swami Veda Bharati and Swami Rama of the Himalayas, including the ideas that progress in yoga involves studying oneself at the level of action, speech, and mind/thought; that this progress takes self-discipline; and that true knowledge comes from direct experience. And the practice itself? Pandit-ji takes one of the yamas or niyamas and makes a commitment to practice it in a particular, concrete way at one level (say, the level of speech) for twenty-one consecutive days. Then he moves on to practice that yama or niyama at another of the three levels (say, the level of action) for twenty-one consecutive days, finally advancing to the third level (mind/thought, for example) for (you guessed it) twenty-one consecutive days. Any mess-up puts him back to day one of whatever level he’s on. Success with one yama or niyama means choosing another, and starting the process from the beginning.

Intimidating? Maybe for some, but totally inspiring for others of us, and his gentle encouragement (and funny examples of his mess-ups) urged us to consider how we might craft similar practices for ourselves. Most of all, his very presence—graceful, serene, sincere—provided the inspiration, showing us, as it did, the end result of the devotion of a true yogi.

The Summer Olympic Games are long over. Nevertheless, I’m still a bit breathless (and not just because now I somehow think that I can actually run fast, or jump far, or spin in place without falling over, and so I try. To pretty ridiculous effect).

The Summer Olympic Games are long over. Nevertheless, I’m still a bit breathless (and not just because now I somehow think that I can actually run fast, or jump far, or spin in place without falling over, and so I try. To pretty ridiculous effect).

It’s the demonstration of courage that had me catching my breath. I’m not just thinking of the courage the athletes demonstrated to get to the games, although of course that courage was—and is—stunning. (Consider, for example, what it took US sprinter Bryshon Nellum, already something of a track superstar as a sophomore in college, to suffer and recover from being shot in the legs after two assailants mistook him for a rival gang member. His doctors said he’d never compete with other world-class athletes, but he did, a mere four years later).

I’m also thinking of the in-the-moment courage of setting up alongside fierce competitors in the starting blocks and seeing the track stretch out to the finish line. It’s the courage of having the hopes of a team, family, or community come with one onto the empty the field. It’s the courage of platform divers who walk to the edge of three-story-high platforms, turn their backs to the pool, press up into handstands, and launch themselves blind into dives that take them to the water at 35 miles per hour. That’s the courage that still makes me swallow hard.

It’s also the courage of another athlete—not yet an Olympian, but a fourth-grade girl who gathered up the heart to take off on her first ski jump and fly.

I stumbled across the video of this brave girl’s first jump a while ago and revisited it as the Olympic champions were swimming, running, diving, rowing and being generally stupendous. Now I am one of who-knows-how-many people who have watched the video nearly 1.7 million times. It’s star, too, is stupendous. From a camera attached the girl’s helmet, we see what she sees—the tips of red skis against a long swoop of white—as she readies herself at the top of the ski jump. She first tries talking herself into pushing off, telling herself that she’ll be fine, that she’ll do it, that “here… goes… something, I guess.” But this isn’t yet enough to get her going down the hill. Behind her we hear the voice of an adult—maybe her coach, maybe her dad, maybe a friend—who gives her advice, assures her that she’ll be fine, tells her what to expect, that it’s like what she’s used to, just longer. While giving her a shot of confidence, this still isn’t quite enough, and fear makes the girl’s voice tremble. Finally, we hear the voice of someone else behind her, another young girl who’s obviously been in the very same position. This calm, knowing voice says, “You’ll be fine.” And then, “The longer you wait, you’ll be more scared.” That wise advice and steady presence gives the young jumper the momentum she needs. In the span of one breath, she says, “Here… I… go,” and she begins her flight.

We all have different fears, and what might take courage for me may be a breeze for you. But surely most of us share the common, more existential fear of failure, whatever our aims may be. Much of what we do feels like flinging ourselves off of a steep drop-off, one intimidating enough to cause us to turn around, take off our gear, and tell ourselves that that we didn’t really want to do it anyway. Or that the goal is stupid. Or that the rest of the world is stupid. Or that we are stupid.

It’s hard to know how to gather the heart we need in the midst of the fear of failure. Milton Glaser, a brilliant graphic designer, offers this bit of advice:

You must admit what is. You must find out what you’re capable of doing and what you’re not capable of doing. That is the only way to deal with the issue of success and failure because otherwise you simply would never subject yourself to the possibility that you’re not as good as you want to be, hope to be, or as others think you are (“On the Fear of Failure“).

Admitting what is; that alone takes courage. I’m grateful to say that seeing and admitting “what is” has been one of the gifts of my yoga practice. In my experience, practicing the yamas, niyamas and asanas has helped me move more gracefully through the world, with more peace, since they have helped me place myself in a more balanced, less dependent and attached relationship with others and with my own desires and expectations. Much of the time, I can hold steady in the face of reality, even scary reality. By practicing pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, and dhyana, I have come nearer to a reality that I never knew I carried within myself: a vastness whose center is pure stillness. Full. Complete. Knowing that this is there all the time makes facing the moments when I’m not practicing somehow easier, even sometimes, somehow grace filled.

Just as we all don’t have the same fears, we all don’t have kind and wise friends or experienced mentors who will cover our backs, offer us good advice and steady assurance, and care if we’re scared or confident. According to the yogic sages, however, ultimately and fundamentally we alone are sufficient. Within the vast stillness inside each of us is an all-knowing self with the wisdom and ability to guide us to our highest good, if only we become quiet and focused enough to hear it.

I’ve learned to listen hard for that voice. Sometimes it speaks loud and clear, and other times… well, not so much. And while I cannot say that I always muster up the courage to step off into the unknown, more and more I walk right up to that edge, stand facing forward, and with eyes wide open, really see what is.

Typically, I don’t watch much television. But like many people, I find the Olympic Games irresistible. The speed of well-trained minds, the physical grace of strong, practiced bodies, the nearly palpable power of concentration… unathletic me finds it awe inspiring. So I made a trip to Radio Shack, untangled a mess of cords, and plugged and unplugged connectors from boxes until London appeared on the screen. Then Fleur the Cat and I settled in.

Typically, I don’t watch much television. But like many people, I find the Olympic Games irresistible. The speed of well-trained minds, the physical grace of strong, practiced bodies, the nearly palpable power of concentration… unathletic me finds it awe inspiring. So I made a trip to Radio Shack, untangled a mess of cords, and plugged and unplugged connectors from boxes until London appeared on the screen. Then Fleur the Cat and I settled in.

Of course, along with the freestyle relays, the beach volleyball matches, the road races, and the skeet shooting come the commercials. I don’t hate commercials; in fact, I admire good ones (and, I must also admit, all too often cry at sappy ones), since part of what I do for a living is write advertising and branding copy. So when I watch, I pay attention. And one commercial running during this summer’s broadcasts kept my attention.

Nike’s “Find Your Greatness” is beautifully filmed, but it was the message that made me search the Internet when the one-minute spot ended. In a nutshell, the gist is this: Somehow, for some reason, we think that greatness is reserved for the gifted, talented, rare few. But greatness doesn’t lie in wait for special people. Greatness is wherever someone is trying to find it.

Greatness is in the trying. It is in the practice. It is in the seeking. This set me to thinking… in my life, trying for what? Practicing for what? Seeking what? And the first answer that popped into my head was this: the experience of wholeness.

It seems so easy for so many of us to see ourselves and to feel ourselves as lacking, as insufficient, as not quite able, or in some way or another as less than. Yoga philosophy promises that at our core, we are always already whole, lacking nothing. But in reality, we just don’t always (if ever) feel it or we just don’t (or won’t) believe it. Nevertheless, yoga science, through things like the eight limbs of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, provides “maps” for those of us willing to put doubt aside and take the chance that yogis across the centuries might just have been right.

Such yogis embraced sadhana to find their greatness. The Sanskrit term sadhana is often used to mean self-effort and the discipline necessary for sticking to a program of spiritual advancement. It is from the verb-root sadh, which means to go straight to the goal, just as Olympic athletes, gathered to compete in the games, go straight for the goal.

The master teacher of a number of my own teachers said this about sadhana:

The process in which the aspirant unfolds, develops, and enlightens himself [sic] is called sadhana. Sadhana is the practice which has the power to carry the seeker (sadhaka) to his objective. The object is to realize the truth of life. We have to bring about our maximum development and arouse and express the power lying dormant within us. It is possible through sadhana alone…. Our goal is to attain absolute peace, an unalloyed happiness or perennial bliss; and this is possible only when we use all circumstances in life, whether good or bad, happy or painful, to promote our sadhana. All circumstances in life cannot be made to suit us, but continuous sadhana makes us feel that the condition which is hostile to us at present, is in fact an opportunity for advancement on the path (Swami Rama, Book of Wisdom: Ishopanishad).

The experience of wholeness (of absolute peace and unalloyed happiness) is possible, so say those great sadhakas who have, through practice, seeking, and trying, found their greatness. And what heartens me is that all aspects of a complex, modern life—the joys and losses, the gifts and griefs—play an integral part.

Feeling whole is not reserved for those with the luxury of taking daily hatha classes or going on three-month-long retreats in sacred places. It is not the privilege of ancient ascetics who sought the silence of meditation caves high in imposing mountains. It is for all of us. My own experience of that wholeness lies in my choosing to live my life, with all it brings me, in a certain way, a way inspired by the wisdom of yoga, a way that is everyday seeking, step by step, and everyday greatness.

A sweet and wise friend, Namita, shared a story with her Facebook pals that went something like this (I paraphrase—and switch up genders, just for fun):

One day, a young Buddhist, on her way home after a long journey, found herself before a wide and mighty river, one that impeded her progress. She spent hours on the bank, trying to figure out how to cross the great barrier.

Feeling hopeless about being able to continue on her journey home, she saw, on the opposite bank of the river, a venerable teacher. She called out, “Oh, wise one. Can you tell me how to get to the other side?” The teacher, thoughtfully considering her answer, called back, “My child, you are on the other side.”

Maybe I find this story so poignant because I just returned home from a two-week-long journey (and very, very nearly missed the return flight). But there’s something else here that strikes home (so to speak). It’s not quite the somewhat clichéd idea that wherever one is, one is already home, but it is close.

I am graced to know a few swamis—great meditators and teachers, each one—who share a common characteristic that I find pretty stunning: they are remarkably emotionally self-supporting. I see this most in their comings and goings. When they arrive from their international travels and teaching, they are filled with happiness and contentment at seeing those of us who welcome them. And when they leave us, they are filled with happiness and contentment in their going.

This has taken some getting used to. After all, one wants a friend, teacher, or loved one to grieve a bit when she leaves, to depart reluctantly, with sadness. But now I find it something to aspire to, since I see it as evidence of a valuable kind of emotional self-sufficiency, a kind of fullness that one feels in a home that is safe, warm, familiar, and welcoming. I, too, want to feel this, wherever I am.

Sometimes the barriers we face are wide and mighty external things like rivers, or wacky airline regulations and requirements, or the emotional reactions of other people. Sometimes they are internal, but no less wide and mighty: fear, doubt, anger, jealousy, laziness, and the like. How does one get home in the face of such obstacles?

For me, the answer is this: I practice. I sit, breathe, meditate, and find that stillness that is not a lack of something, but that is fullness itself, that is the full presence of the ever-wise inner teacher. Then I consciously impress what this feels like into my memory, so that when I venture out into the world again, I can always arrive back home, especially when it seems farthest away.

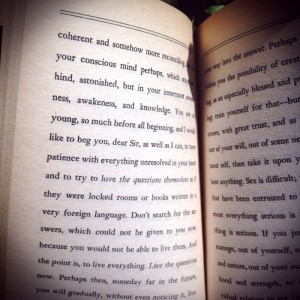

There is so much in the work of the late nineteenth-century, early twentieth-century German poet Rainer Maria Rilke that I find astonishing—that cracks open my everyday perspective, simply and powerfully. Some of his most accessible and moving (and now very well-known) words are in his letters to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young military student who was embarking on a career he wasn’t sure he wanted when he sent the famous poet a letter of introduction and a few pages of his own poetry. In one of his letters back to Kappus, Rilke writes,

There is so much in the work of the late nineteenth-century, early twentieth-century German poet Rainer Maria Rilke that I find astonishing—that cracks open my everyday perspective, simply and powerfully. Some of his most accessible and moving (and now very well-known) words are in his letters to Franz Xaver Kappus, a young military student who was embarking on a career he wasn’t sure he wanted when he sent the famous poet a letter of introduction and a few pages of his own poetry. In one of his letters back to Kappus, Rilke writes,

You are so young, so much before all beginning, and I would like to beg you, dear Sir, as well as I can, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer. (Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, trans. Stephen Mitchell)

So again, here’s patience—with the mystery of our most unresolved, anguished questions, those lodged in our hearts as if locked in rooms or as if lying just beyond our comprehension on the pages of a seemingly (very) untranslatable book. Clearly knowing the discomfort of holding those questions himself, the poet gently advises his young friend to try to love them. Not to love them, but to simply try. And then to wait, maybe for a really, really long time, for the answers to become visible, tangible, livable.

For Rilke, the waiting erupted into poetry.

One of the biggest challenges for me in my practice of yoga has been that, when it comes down to it, the learning‚ the discovery, and the baby-step-by-baby-step resolutions are all essentially and fundamentally experiential. For an ex-academic inclined to hoard reference materials and to do impressive amounts of research before embarking on just about anything, this is a huge deal.

And this is why Rilke’s advice moves me, and why it is so important for me. Every time I close my eyes before meditation practice or move into an asana or slow and deepen my breath in pranayama, I am struck (I swear it often feels physical) by how “so much before all beginning” I am, especially in the face of the enormity of my endeavor and its importance. The practice and the reason for the practice are everything, and it is often like stepping into darkness; I cannot see where I am going. How I respond is my choice: I can turn back, I can fume, I can give into doubt, uncertainty, or fear, or I can present my questioning self, do what I know, wait, and cultivate patience. It’s not easy; I am waiting to “come into” the answer of the meaning of my existence—or more accurately, I am waiting for the answer to come into me, living in the urgency of the question, trusting that the answer will come, probably piece by piece, when my practice has prepared me to live it. And I don’t know when this will be.

Yoga philosophy, of course, promises that each of us already has the answers and they comes to us from within. So perhaps I should say that I wait for the answers to emerge into my self-awareness, to crack that perspective open so that I live everything even more fully than with the questions alone, as more of who I truly am.

If all of this is too heady, or all of this stuff about patience and waiting and emerging self-awareness just too wearing, we can come back to the things that the practice gives us as we do it. When it comes to meditation, the ongoing fruits are something like these (in the words of a master yogi and teacher):

Meditation will give you a tranquil mind. Meditation will give you awareness of the reality deep within. Meditation will make you fearless; meditation will make you calm; meditation will make you gentle; meditation will make you loving; meditation will give you freedom from fear; meditation will lead you to the state of inner joy called samadhi. These are the results of meditation. If you understand these goals and want to meditate, then it will help you… (Swami Rama, The Art of Joyful Living)

Rilke says in yet another letter, “What is happening in your innermost self is worthy of your entire love.” All the practice, the sitting with the questions, the trying to love them, the failing or the not failing . . . all of it is worthy of our deepest devotion—every drop of it. For each of us is, after all, so worth being, and so worth waiting for.

Earlier this week, I came across a quotation that picked me up, shook me around a bit, and then plopped me back down. (I love when this happens.) In the book The Spirituality of Imperfection (a title that, when I first saw it, already gave me the “this is important” shivers), Ernest Kurtz and Katherine Ketcham write,

We modern people are problem-solvers, but the demand for answers crowds out patience—and perhaps, especially, patience with mystery, with that which we cannot control. Intolerant of ambiguity, we deny our own ambivalences searching for answers to our most anguished questions in technique, hoping to find an ultimate healing in technology.

I am certainly a problem-solver and answer-demander, but have always thought that I scored pretty high on the patience scale. I’ll stick to a task until it’s done. I’ll go slow and steady if I have to. I’ll be the one to cross the finish line, to get the degree, to bide my time until an answer is confirmed. That’s patience, right?

Well, maybe. Sometimes. But other times it’s just willful stubbornness laced with “I’ll show you” and spiked with exactly what Kurtz and Ketcham find to be such a problem: an intolerance of ambiguity (as in, “What do you mean ‘Will this work?’ Of course this will work. I’ll show you—even if it kills me.”). I know this pattern in myself. It’s what got me through graduate school. But I’m not all that comfortable with it anymore. I’m much more interested in cultivating true patience, even (and perhaps especially) patience with mystery.

There doesn’t seem to be one term in Sanskrit that captures just what we mean by the term “patience.” Abhaya points to the fearlessness that patience sometimes requires, and dhairya denotes firmness or steadiness, which captures another aspect of patience. But kshama may be closest, as it can mean forbearance, a term often used in English as a synonym for patience. Like most Sanskrit terms, however, it’s meaning is layered, for it also means forgiveness.

So to have patience with yourself or another person is not only to forebear frustration, or discomfort, or whatever feeling the situation triggers in you, but to also forgive. How difficult, but how beautiful.

Even with our more basic understanding of patience, we tend to find it difficult to cultivate. We’re problem-solvers, sure. But yoga philosophy suggests an even deeper root: attachment. Our setting of expectations, and our attachment to finding “solutions”—especially solutions outside of us—precede the problem-solving. We wonder why we’re not happy, and turn to certain other people or things to solve the problem. When that doesn’t work, we turn to yet more people—or jobs, or cities, or pieces of pie, or whatever.

Why? Kurtz and Ketcham suggest that we’re intolerant of ambiguities and we deny our own ambivalences. I think they are on to something. We’re uncomfortable in that place of suspension, feeling an equal pull between two opposites. We’re uncomfortable fluctuating between what strikes us true but what could be false, between something we find both attractive and unattractive. When we’re stuck in the middle of a river, we tend to call whichever bank seems closest the “right” or “best” bank.

In our meditation practice, this intolerance can show up as giving up on certain techniques or sitting postures—or giving up the practice altogether—when we don’t experience exactly what we expect. But of all things, meditation puts us face to face with mystery, and to complicate this mystery, we often look to meditation to answer our most anguished questions: Who am I? What is my purpose? And so meditation is the quintessential activity for the cultivation of patience. Journeying into—and beyond—the unconscious mind, with all the other things that this requires and entails, means bumping into ambiguity after ambiguity after ambiguity. And while we can learn of the meditative experiences of others, ultimately our own experiences will be absolutely unique. Others can provide a kind of roadmap, but we must take the steps. What those steps will be like for each of us depends on who we are. And self-discovery takes patience.

I don’t mean to suggest that we should stick with something or someone if it isn’t working for us or if it’s harmful. But as one of my teachers is fond of saying, the mind is like a laboratory, and as meditators, we are scientists of the mind. The best scientists don’t assume what they’ll see; they formulate hypotheses. They don’t demand solutions; they test and observe. And then they test and observe again. This technique of problem-solving doesn’t crowd out patience; rather, it requires it and allows it to flourish. And it helps scientists see their way forward.

These days, as I take my meditation seat, I practice that kind of patience, the patience of the explorer, the patience of the scientist. I test and observe and forgive myself my flares of impatience, all the while keeping an eye on the roadmap of the great meditators who say that, as one practices in this way, the highest part of the mind, the buddhi, the intuitive intelligence, helps guide the way.